The two rules of editing

Editing is very subjective, and it’s a delicate situation. Most authors are touchy about their work, and quite rightly. Expressing yourself on the page is a reflection of who you are. And when you’ve worked hard at something for probably years, it’s hard to just take criticism in stride.

Editors who aren’t writers themselves are often a bit cavalier about this. And they don’t get much training. In fact, Allegra wrote How to Edit and Be Edited after working with an author who had refused to make the changes his previous editor recommended, because, as he said, “I didn’t even know if she liked the book.”

So, to become a better editor yourself, and to know what to ask for from those who read your writing, remember these two rules:

Praise.

Ask questions.

Praise

Many people are under the impression that editing is about criticizing. Yes, it’s about identifying what can be improved, but if you take a critical approach immediately, the result is a defensive author who closes their ears.

When you lead with praise, you’re demonstrating that there’s something about this writing that you like. (If there’s nothing, you’re not the right editor for it.) The author gets a better understanding of what they’re doing well, and they know you appreciate it. You’re also setting a realistic benchmark for the material that you’re going to suggest needs improvement. The author knows that they can write at least this well, and they’re motivated to bring the whole thing up to this standard.

Ask questions

Many people are also under the impression that it’s the editor’s job to improve the author’s writing. It isn’t. It’s the editor’s job to help the author improve their writing.

The classic example of bad editing is very common: the film development executive who says, “You need a car chase here.” (I’ve actually had that said to me.) They’re not identifying a problem; they’re leaping to a solution that very likely won’t be the right one.

The author may have already tried that solution and it didn’t work. That solution may not make any sense in the plot chain of cause-and-effect. Worst of all is that an author who is told what to do by someone who doesn’t care about the work as deeply as they do, and doesn’t respect their authorship, is going to do one of two things: a) get sullen and lose motivation; or b) try to please and lose their originality and authenticity.

The editor’s job is to identify problems, not to present solutions. So the best strategy is to identify the problem by giving plain information on your response as a reader—”I don’t understand why the character is doing this,” or, “this feels repetitive,” or, “the momentum has disappeared”—and then ask questions.

“Why is the character doing this? What do they want?”

“What could make this incident build on the previous one, instead of repeating it?”

“Given what just happened in the story, what action would this character take?”

“What’s at stake here?”

We find that the best ideas arise in the conversation between author and editor as long as both have only one agenda: to make the work as good as it can possibly be.

Writing Advice:

How to Edit Your Own Writing

And Other People’s Writing, Too

The Imaginative Storm method is all about generating fresh, original, authentic material. Then what?

Well, that may be all you require for your own creative satisfaction. But if you want to publish your writing, you’ll want to make it as good as it can possibly be before it goes out of the house.

For a full discussion of editing, check out How to Edit and Be Edited by Allegra Huston, bestselling author, Imaginative Storm co-founder, and previously Editorial Director of one of London’s top literary publishing houses. Here’s the short version.

Getting feedback on your writing

Getting a fresh eye on your writing is essential. It’s very hard to be objective about your own work. If you know a good professional editor and have the money to hire them, do it. The chances are you don’t, and you’ll turn to your circle of friends and acquaintances.

Choose carefully. Don’t give your unedited work to anyone who will have an agenda: a sibling, a parent, a competitor. Only give your writing to people you can trust to be both honest and kind. If you’re asking someone to read a full-length book, be aware that this is a big ask: 10 hours or more of their time. So if you can, ask people for whom you can return the favor.

We suggest having three people read your work. If you have three opinions, you can see where they agree and where they differ. And even when they differ (one person says cut this, another says expand it), they’re likely trying to solve the same problem in different ways. You can triangulate these responses to figure out what the problem actually is—and maybe the solution will be something entirely different.

But before you do this, know what good editing is and become a better editor yourself. That way, you can give your readers guidance on how you want their feedback to come to you.

Line editing and copyediting

Line editing and copyediting are different. A line editor will cut and change words to make the sentences smoother, more euphonious. They’ll cut repetition of words and phrases. They may even rearrange paragraphs.

If you’re line editing, it’s a good idea to put a comment in Track Changes saying something like, “What do you think of this?” or “Suggest delete.” You don’t want to sound like a teacher correcting a sixth-grader. You want the author to know that you’re on their side, not setting yourself up as their judge.

Copyediting fixes mistakes of spelling, grammar, word usage, and punctuation and focuses on consistency throughout the manuscript. Many things are still a judgment call, because English is a very freeform language, but you’ll accept most of the changes a good copyeditor makes. Good copyediting is one of the biggest differences between a professionally published book and a self-published one. So if you’re self-publishing, don’t skimp on this step. Hire a professional.

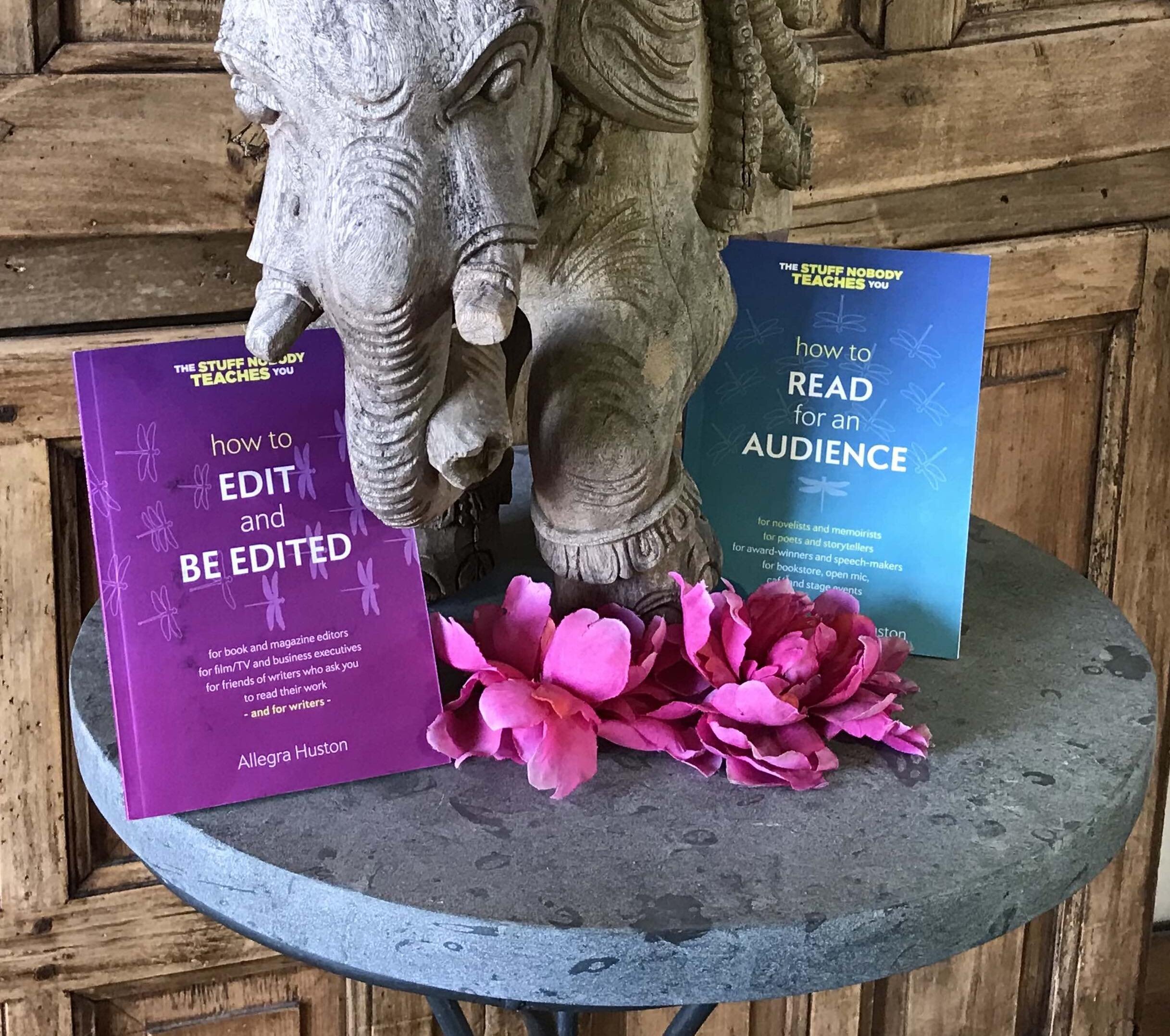

Our books for writers

How to Edit and Be Edited and How to Read for an Audience are available in paperback and digital download from our website, and can also be ordered wherever books are sold, anywhere in the world.

Both are also available on Kindle and other e-book platforms.